The Global Earth System

Our Earth is a global system on which all human life relies. However, academics have identified various Tipping Points, which if triggered can irreversibly change the Earth system. Tipping Points show that the overall threat posed by the climate and ecological crises is far more severe than is commonly understood.

The triggering of Tipping Points will have wide-ranging impacts – to give one example, the collapse of the Atlantic Ocean’s great overturning circulation (AMOC) could cause half the global area for growing wheat and maize to be lost. Other effects could be even more catastrophic.

One major concern with Tipping Points is that the effects cascade through to global economic and social systems. And currently, there is no global governing body set up to deal with the systemic, and widespread impacts that crossing these Tipping Points could cause.

Tipping Points may create abrupt change that we cannot adapt to fast enough, and conditions would change irreversibly. Over time, this would make our world much harder for humans to survive on.

There are five major Tipping Points that are already at risk of being crossed: the Greenland ice sheet, West Antarctic ice sheet, warm-water coral reefs, thawing permafrost, and the North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre (SPG) circulation.

However in this article, I’d like to discuss the Amazon forest dieback Tipping Point.

Amazon Forest Dieback

The Amazon is a globally unique region of exceptional geodiversity and biodiversity. It hosts the most diverse tropical forest on Earth and 10% of the world’s biodiversity and is home to roughly 1.5 million Indigenous People.

Tipping Points force us to consider effects on a much larger scale. They are effectively about the switching of a system from one state to another.

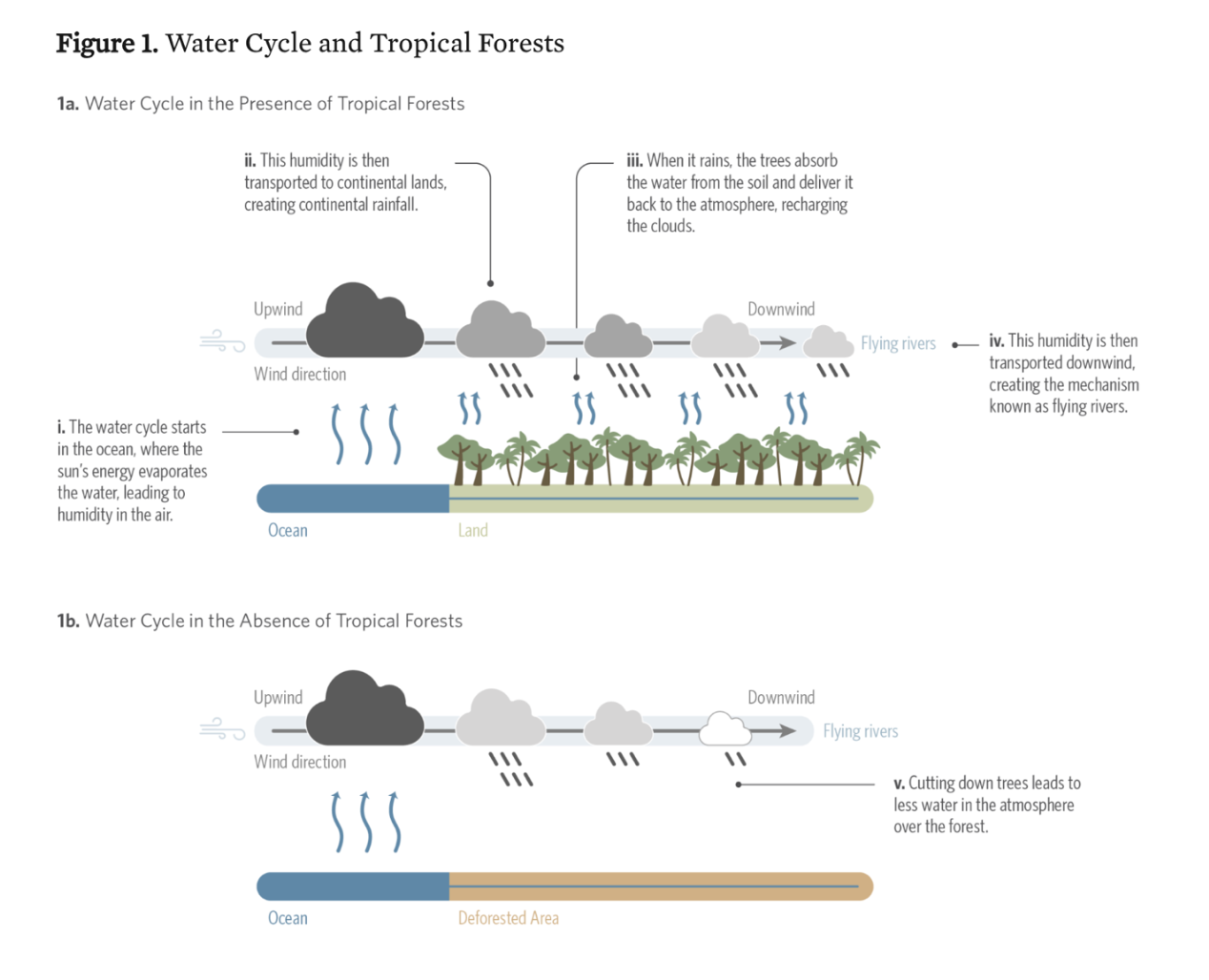

In the case of the Amazon Forest Dieback Tipping Point, when land is deforested to a certain extent the water cycle is disrupted. Instead of rainwater being recycled back to the atmosphere via trees, more than 50% of rainwater runs off. With insufficient moisture in the atmosphere the tropical forest is then irreversibly converted into a savannah ecosystem. This not only impacts the forest, but also farmland – as rainfall decreases, which is needed to sustain crops. You can see this illustrated in the diagram below.

Source: Climate Policy Initiative.

Source: Climate Policy Initiative.

What are the risks of Amazon Dieback?

Savannization of the Amazon threatens biodiversity, energy, food security, and carbon removal.

Driven by the cascading effects of land use and climate change, Amazon Dieback would prevent primary and secondary forests from removing almost 1 billion tonnes of CO² per year and recycling up to 50% of rainfall, and would actually turn the region into a permanent carbon source.

If the Amazon rainforest reaches its Tipping Point, the cumulative economic cost could reach around $256.6 billion in lost GDP by 2050 – impacting countries like Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Bolivia, and Ecuador most significantly.

These five Amazon countries amass 70% of their GNP from agribusiness, hydropower, and heavy industry. The rainfall the Amazon generates is crucial to these industries, and thus the livelihoods of countless people across Latin America.

The single biggest economic shock will come from the loss of hydroelectric power capacity, following a collapse in the quantity of freshwater. If the Tipping Point is passed, power generation potential will decline to almost 70% below its maximum level.

Water quality is also expected to decline by roughly 25% due to droughts and increased erosion, increasing health insecurity in the region.

Credit: Open Planet.

How close are we to the Amazon Tipping Point?

If deforestation exceeds 20–25% of the Amazon original cover, the Tipping Point is expected to be reached. The rainforest’s water cycle could collapse, releasing 150–200 billion tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere, decimating biodiversity, and disrupting global weather systems.

Amazonian deforestation is currently at ~17%, so the Tipping Point is (at most) 20 years away – at the current rates of destruction – giving us only this decade to act.

What’s next for the Amazon?

This existential issue needs the entire global community to prioritise the economic value of a standing tree in the Amazon, over one cut down.

We need everyone to understand that there is no possibility of limiting global temperature increase to 2°C, without halting emissions from forest loss. And we need to take the risks associated with triggering Tipping Points far more seriously.

We need all business sectors and financial institutions to come together around this issue before it is too late.